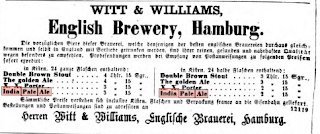

"The excellent beers of this brewery, which are on a par with those of the best English breweries and are a favourite drink even in England, are particularly recommended because of their pure, healthy, and nutritious quality."

Wednesday, March 23, 2022

A Pair of Englishmen Abroad

Tuesday, March 15, 2022

A Bohemian Porter?

Once upon a time I was sat in a brewpub in Brno. On the wall of the brewpub, called Pegas since you ask, was the following sign:

For those unversed in the Czech language, the sign reads "Original Porter from České Budějovice, from the City Brewery". On the opposite wall was the same sign in German, in which "Měšťanské Pivovaru" was "Bürgerliches Brauhaus Budweis", or the brewery known today as Samson, originally founded in 1795. The idea of Bohemian Porter has kind of intrigued me ever since.

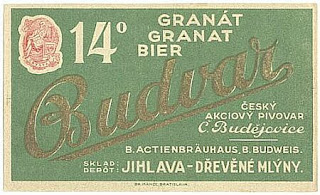

When I lived in Czechia there was basically just one Bohemian Porter in regular existence, the delightful 19° Pardubický Porter, but when I was digging around in Pivety.com, I came across several labels for other Bohemian made porters, such as Třeboňský, Brněnský, and more Budweiser Porter.

There are plenty of other examples that show porter being brewed in Bohemia was most definitely a reality before the descent of the Iron Curtain in 1948. Clearly from the gravities on the labels, porter was a strong dark beer with a gravity of, at least, 19° Plato, which is basically the modern Czech description of a porter.

The thing that often played on my mind was whether the Bohemian Porter of the late 19th/early 20th centuries became the modern tmavé pivo, and I was never convinced. Tmavé is, after all, just a colour descriptor, it doesn't denote the strength of a beer, it's bitterness, or even its point of origin, it is just tells you to expect a dark beer. Even then, it can fall on a colour spectrum from deep red to pitch black, and some lagers marketed as "tmavé" are paler than other breweries' polotmavé, that's amber, beers. It seems as though porter stood apart from the morass of tmavé, with its strength being a key differentiator.

As I have been digging into various newspapers and journals in the Austrian National Library's newspaper archive, I have come back time and again to "Der Böhmische Bierbrauer", the journal of the Brewing Industry Association in the Kingdom of Bohemia. It was here that I found another part of the porter story...a recipe of sorts, and the beginnings of a process.

So I set about trying to understand what was going on in this, according to the article's author, "well known brewery whose products are highly esteemed and sought after". In the same article, the author discusses "märzenbier" and "kaisersbier" as well.

Anyway, we start with the grist, 2250kg of malt kilned to 76° Réaumur (about 95° C), which thanks to information from Andreas Krennmair would be in the ball park of Munich malt, and 175kg of "Farbmalz". "Farbmalz" literally translates as "colour malt", a phrase in Czech that is still used today - "barevný slad". Farbmalz can also be known as "rostmalz", which is obviously "roasted malt", so we are talking about something similar here to Carafa malts, whether I, II, or III, I really don't know, but that's the ballpark we are playing in. And that's it, a simple grist of 92.8% Munich malt and 7.2% roasted malt.

The grist goes into 48 hectolitres of water, that's 1109 US gallons, or 924 Imperial gallons, a mash then of 1.7 litres of water per kilo of grain. Being an article in the official organ of the Bohemian Brewers' Association, I am going to assume that certain process elements were simply understood and thus not written down. Thankfully though, the author does use the magical incantation of "Dreimaischenmethode", a literal translation of which would be "three mash method", but remember where we are and to whom the author is communicating, and here we have porter being made with a triple decoction mash. We are not told what temperatures are being targeted, but again his audience probably didn't need that level of detail, just do a triple decoction mash, with the first decoction being boiled for 25 minutes, the second for 30, and the third for 20, mashing out at 59° Réaumur (73°C/164.7°F). Oh, and during the third decoction add 52 kilos of hops, assuming here that the hops were added to the decoction while it was boiling, there would have been some isomerisation of the alpha acids to contribute bitterness - but here I am kind of at a loss, so if anyone can explain this better, that would be great.

If I understand the German correctly, the pre-boil gravity was 17.8° Plato, working on the assumption here that "°S" is shorthand for "grad Stammwürze", which post boil came to 22.2°P. With the wort vatted for primary fermentation, it was held at 5.5° R (7°C/44.6°F) for the first 9 days, and then allowed to rise in temperature to 9°R (11°C/51.8°F) for a further 9 days. After 18 days of primary fermentation the finishing gravity was 9.6° P, giving our Bohemian Porter an abv of 7.2% going into the lagering process, which lasted 10 months.

Now, I am not saying that I have an iron clad recipe for porter as being brewed in Bohemia, mainly because I am not the audience for this journal and thus there are gaps in my knowledge, but I think this shows that Porter was understood in Bohemia as a strong, dark, well aged, lager, and was more than just a curiosity. Wonder if I can persuade someone to try making one...

Friday, March 11, 2022

Of Bohemia and Bavaria, with a Taste of Austria

It is sometimes difficult to imagine more iconic beer, specifically lager, brewing regions of the world than Bohemia and Bavaria. Likewise difficult to imagine is a more iconic type of lager from Bohemia and Bavaria than the pilsner. Further, is there a more recognisably Austrian family than the Von Trapps?

Von Trapp Brewing up in Vermont currently have a special release of their Bavarian Style Pilsner, so I figured I'd take the opportunity to do a little side by side tasting of that and their core Bohemian Pilsner...first up, Bavaria.

- Sight - golden, beautifully clear, good inch of white foam that persists nicely

- Smell - floral hops, lightly toasted grain, lemon oil, graham crackers

- Taste - rustic, crusty, bread, some lemony bitterness, very subtle spiciness in the finish

- Sweet - 2/5

- Bitter - 3/5

An absolutely lovely beer, and more than justifying the fact that I bought a couple of cases when it finally made its way to Beer Run. It was this beer I had in mind when I tweeted something along the lines of the best beers those that you can drink a few ounces of to write your tasting notes, and then just sit back and enjoy the beer, making the occasional note as thoughts come to you. It has a really nicely rounded mouthfeel that complements the medium body perfectly. The lemony hop bite in the finish is just perfection in my mind, and the finish is not overly dry, but definitely clean and sharp. There are times I wish this were a core part of the Von Trapp range, not in the sense that it should replace any of their other wonderful beers, but be added to them.

Onwards them to Bohemia.

- Sight - paler than the Bavarian, dark straw, 3/4" of white persistent foam

- Smell - spicy hops, some herbal notes, nice note of fresh hay, slightly grainy

- Taste - crackers, sweet grass, really solid hop bitterness, almost pithy

- Sweet - 2.5/5

- Bitter - 3/5

Wednesday, March 2, 2022

Beyond Definition

I have seen several examples of "světlý ležák" that would be regarded in Czechia as "světlý speciál", given their starting gravities above 13°.

— Alistair Reece (@Fuggled) February 25, 2022

Trying to shoehorn central European categories into an Anglo-American taxonomy is fraught with the potential for misunderstanding.

This train of thought, combined with something I read in Der Böhmische Bierbrauer about the fact 10° beers were by far the most commonly produced in 1890s Bohemia, got me wondering what exactly is a 10° beer, other than having a starting gravity of 10° Plato?

According to Czech beer law, there are 4 types of beer:

- Stolní pivo or 'table beer', up to 6° Plato OG

- Výčepní pivo or 'tap beer' between 7° to 10°

- Ležák or 'lager' 11° and 12°

- Speciální pivo or 'special beer' 13° and higher

Fuggled Beers of the Year: BOAB

Audience meet BOAB, BOAB meet audience. If it is your first time meeting BOAB, you might just need to know that it is Fuggled-speak for beer...

-

I was wandering around the supermarket where I do the weekly shop recently, and as is my wont I bimbled over to the beer section to have a b...

-

This month's iteration of The Session is being hosted by Ray and Jess over at Boak and Bailey, and the theme they have presented us wit...

-

At the beginning of this year, I made myself a couple of promises when is comes to my homebrew. Firstly I committing to brewing with Murphy ...