When I lived in Czechia, the website expats.cz provided a useful and occasionally fun way to garner inside information on living in that foreign land about which, at first, I knew nothing. Once upon a time, the site had a message board which was split into themes like "Accommodations", "Life in CZ", and the ever popular "Miscellaneous" - possibly not exact titles, but you get the drift.

It was not uncommon to see grizzled old hands rolling their cyber-eyes at the latest newly minted TEFL teacher/poet/novelist looking for a place to get a distinctly foreign product to make their new life in central Europe more akin to their home country. I know of people, and I am not exaggerating here, who whenever friends visited from the UK had them bring British milk and bread. It was just as often on the boards to see comments along the lines of "if you don't like it go home" as the 9 millionth newbie complained about Czech service.

Prague, being an international hub, was home to all manner of ethno-pubs, butchers doing "proper" bacon and sausages (which were superb by the way), places to buy Wychwood ales, and places to get cheese from across Europe. There were even a couple of Marks and Spencer stores. Fun fact there was an M&S in Prague when I first arrived in 1999, it was out at Černý Most and didn't have a food hall, ergo, it sucked.

These message boards popped into my mind as I was bimbling around the scanned newspapers of the Austrian National Library, in particular the weekly "Česká Vídeň", which from what I can see was published from 1902 to 1914, but scans only exist from 1907 to 1909. "Česká Vídeň" translates as "Czech Vienna" and obviously thus served the sizeable Czech community in the capital of the then Austro-Hungarian Empire. Another fun fact, Vienna was home to the second largest Czech community in the world in the early 20th century, the largest being Prague. Estimates range from 10-30% of the Viennese population in 1900 being Czech, and even today it is not uncommon for Austrians to have distinctly Czech family names.

Restaurants are, I guess by nature, the perfect venue for expat communities to gather in and feel a little bit "normal" or at home in their foreign domicile. As such, it was restaurant ads that caught my eye most, for example...

At Restaurace Fr. Němečka, or František Němeček's Restaurant you could get all manner of Bohemian treats, while enjoying the irony of your host being a Mr Frank German. Mr Němeček naturally sold "delicious export lager" from Plzeň, but not from Pilsner Urquell, rather from the Kladrubský Pivovar which was based in a one time Benedictine monastery. On the food front, his menu featured such "delicious Czech cuisine" staples as tripe soup, liver sausage, and blood sausage - other than the tripe soup, you bet this Scotsman would have been there, jitrnice and jelítka are some of my favourite Czech foods. Mr Němeček, being a most congenial host, naturally invites you to visit.

If you were looking though for a choice of beers made in Bohemia, you could always try Strozzigasse 22 and Restaurace U Slunce.

Pitching up "At the Sun" Restaurant, you would be welcomed to an elegantly decorated venue by Mrs Langmaiera (née Němcova), who as well as serving delicious Czech cuisine (is there any other kind?), can offer you a choice between Pilsner Urquell, "of excellent quality" and beer from the brewery known today as Budvar.

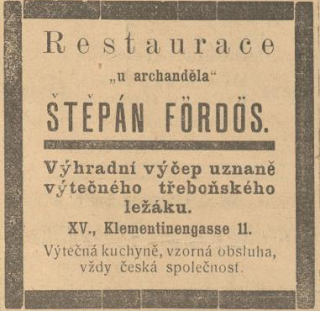

Not keen on making a decision between Pilsner Urquell and Budvar? Then perhaps you want to to visit the divine "Restaurace u archanděla" on Klementinengasse, where your host is a Mr Štěpán Fördős.

I am no expert on these things, but the family name "Fördős" looks distinctly Hungarian to me. A reminder that Vienna was capital to a multi-ethic empire, and that despite the prattlings of nationalists everywhere, none of us are pure anything other than human. At the Archangel is, if my Czech isn't entirely letting me down, the exclusive Vienna tap room for the renowned lagers from Třebon, also know as Wittingau and likely the brewery owned by the noble Schwarzenberg family, known today as Bohemia Regent. Of course, just like most of the restaurants whose ads I saw, the Archangel promises excellent food, though the "exemplary service" was new, as was a phrase I saw pop up time and time again..."vždy česká společnost".

"Vždy česká společnost" translates literally as "always Czech company", which I have to admit had me scratching my head at what it meant. The word "společnost" does indeed mean company in the sense of a corporation or business, so was the advertiser claiming to be an "always Czech owned company"? The more ads I read though, the more it became apparent that "společnost" did indeed mean company, but in the sense of "community" or "fellowship". These restaurants, like expat hangouts since time immemorial were offering Czechs in Vienna a Czech environment in which to feel at home. Pretty much each and every restaurant ad I saw in "Česká Vídeň" mentioned the beer being poured, and also that they had Czech language magazines available. Rarely did an advert mention any of the dishes being prepared in the kitchen though.

Restaurants were, for Czechs in Vienna, a place to drink Czech beer, read news in Czech, meet fellow Czechs, and eat Czech food, places to have a sense of home away from home. Multiculturalism is nothing new, people have always migrated for better lives, more opportunity, or even just for plain old adventure. I wonder if there were folks in these restaurants who told Honza, having just got of the train and adjusting to life in a modern, chaotic metropolis that if he didn't like it, he should just go home? Probably, but at least there was "vždy česká společnost" to make him feel that he belonged, and another glass full of whatever Bohemian beer was on tap.